mini cases

Reading a case study and not sure what to do?

Let's say you are reading a case study but you aren't sure how to deal with it. On the one hand perhaps the case study presents basic statements of facts, or perhaps the case presents so much rich context that it is difficult to see the underlying challenges. Each case usually includes some leading questions that you can choose to answer and you can extrapolate and investigate wider issues on your own initiative. One of the goals is to respond and recommend based on evidence, usually evidence you will have gathered yourself (aka research). Consider case analysis as a process in which the learner poses or structures the problem, explores and shapes solutions to the problem. A reflective turn on the "case as a process" raises the circumstance where the "problems" that the case raises can be construed as personal knowledge gaps. Problem solving implies an underlying personal process of learning.

When a learner asks "why?" Often the last thing they want or need is for the answer to be given to them. What we as teachers should enable, is not to provide answers to questions, but to facilitate learning through personal discovery. So when someone asks "why?", a good answer might be "I don't know, but I think I might know how to start the process of finding an answer".

In order to put some shape on this as a process consider the following "moves":

In summary: The simplest or simplistic approach is to view each case as a problem to be solved, kind of like a maths problem, assuming that there is or are solutions. Please note; each case is based upon an historical incident or situation and evolved subsequently with its own particular outcome. Consequently, we do not provide solutions or correct answers that resolve the cases.

Instead, each learner is expected to approach a case as if she/he is involved in it as an observer-advisor and can assume that their advice may be acted upon, but only if they are able to justify their prescription with convincing arguments, evidence, knowledge etc.

When a learner asks "why?" Often the last thing they want or need is for the answer to be given to them. What we as teachers should enable, is not to provide answers to questions, but to facilitate learning through personal discovery. So when someone asks "why?", a good answer might be "I don't know, but I think I might know how to start the process of finding an answer".

In order to put some shape on this as a process consider the following "moves":

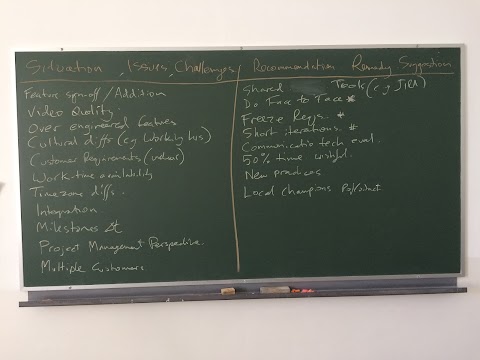

- Diagnose: Identify the problems(s)

- Discover: Independently research the problem area(s)

- Develop: Propose a response or responses, recommendations to resolve, improve etc.

In summary: The simplest or simplistic approach is to view each case as a problem to be solved, kind of like a maths problem, assuming that there is or are solutions. Please note; each case is based upon an historical incident or situation and evolved subsequently with its own particular outcome. Consequently, we do not provide solutions or correct answers that resolve the cases.

Instead, each learner is expected to approach a case as if she/he is involved in it as an observer-advisor and can assume that their advice may be acted upon, but only if they are able to justify their prescription with convincing arguments, evidence, knowledge etc.

- At the most basic a student will understand what happened, who was involved, and get a sense of the general problem(s) as presented. Trivial recommendations, prescriptions, or recipe solutions apply a basic common sense approach e.g. communication breakdowns lead to problems, therefore we need more and better communication.

- However the cases are more amenable to specific analysis under the thematic topics of the subject. You might therefore attempt to apply one or more of the approaches being learnt, e.g. specific communicative structures need to be applied, weekly conference call, meeting minutes, shared CRM database, etc.

- Deeper analysis would go further and do independent investigation; uncover examples, other cases, or templates that might be recommended, e.g. specific meeting format, studies of genres of communication, studies of misunderstanding attributed to specific cultural norms, examples of actual CRM databases and assessment of their feasibility/usability.

- More interesting still is to use the problem case exercises to uncover personal knowledge gaps, and then address them yourself through a rigorous documented process of independent research, perhaps evidenced by a brief statement or report, e.g. "I really knew nothing about contracts so I went and found examples of time and materials, fixed price, and joint venture contracts. I also found a study by Fink et al (2013) that deals with specification volatility in FP and T&M contracts."

Case based learning

The following are highly structured processes for case analysis. You will probably have your own approach or adapt and modify the steps to suit the your own style and conditions.Schwartz et al. (2001) outline a typical sequence of learning-centred activities for case analysis.

- First encounter a problem ‘cold’, without doing any preparatory study in the area of the problem.

- Interact with each other to explore their existing knowledge as it relates to the problem.

- Form and test hypotheses about the underlying mechanisms that might account for the problem (up to their current levels of knowledge).

- Identify further knowledge gaps or learning needs for making progress with the problem.

- Undertake self-study between group meetings group to satisfy identified learning needs.

- Return to the group to integrate the newly gained knowledge and apply it to the problem.

- Repeat steps 3 to 6 as necessary.

- Reflect on the process and on the content that has been learnt.

- Clarify unknown terms or concepts in the problem description.

- Define the problem(s). List the phenomena or events to be explained.

- Analyse the problem(s). Step 1. Brainstorm. Try to produce as many different explanations for the phenomena as you [can] think of. Use prior knowledge and common sense.

- Analyse the problem(s). Step 2. Discuss. Criticize the explanations proposed and try to produce a coherent description of the processes that, according to what you think, underlie the phenomena or events.

- Formulate learning issues for self-directed learning.

- Fill the gaps in your knowledge through self-study.

- Share your findings with your group and try to integrate the knowledge acquired into a comprehensive explanation for the phenomena or events. Check whether you know enough now.

- Initial analysis: identify problems, explore extant knowledge, hypothesise, identify knowledge gaps

- Independent research: research knowledge gaps

- Synthesis: present findings – relating them to the problem(s), integrate learning from others, generate a synthesis, self-assessment of learning process, repeat ‘triple jump’ if needed.

You can also try one or more of the following methods to capture and order your analyses, diagnoses, recommendations etc.

Discover the issues...

Discover the issues...

- Create an Empathy Map (from a key actor's perspective: the person, what they see, say, do, feel, hear, think)

- Brainstorm

- Anti-problem (state the antithesis to the problem and resolve it)

- Context Map (depict rich context)

- History Map (depict the past)

- Low-Tech Social Network (sketch relationships between actors)

- Storycard the Problem(s)

- Draw the Problem(s) (graphical system depiction or representation)

- Stakeholder Analysis

- The 4 Cs or the 4 Ds or the 5 Whys (components, characteristics, challenges, characters; or discover, design, damage, deliver; or ask why 5 times)

- The SQUID (sequential question and insight diagram)

- Root cause analysis (cause-reason fishbone diagram)

- GRAVE, W. S., BOSHUIZEN, H. P. A. & SCHMIDT, H. G. (1996) Problem based learning: Cognitive and metacognitive processes during problem analysis. Instructional Science, 24, 321-341.

- SCHWARTZ, P., MENNIN, S. & WEBB, G. (Eds.) (2001) Problem-Based Learning: Case studies, experience and practice, London, Routledge.

0 Comments